|

KNOW YOUR RIGHTS

Patriot act 2 and 3 come after the next event put on by Bush's:

Executive

Order ..10999

Allows the government to take over all modes of transportation

Executive

Order ..11000

allows the government to mobilize civilians into work brigades under government supervision

Executive Order ..11921

Provides that the President can declare a state of emergency that is not defined,

and congress cannot review the action for six months

Senate Bill ..1873

Allows the government

to vaccinate you with untested vaccines against your will

The FDA says American do not have the right to know which

foods are genetically midified

Congressman Sensenbrenner's bill (HR 1528)

requires you to

spy on your neighbors, including wearing a wire, refusal would be punishable by a mandatory prison sentence of at least two

years

The government claims the power to seize all financial instruments: currency, gold, silver, and everything else if

they deem an emergency exist.

The Patriot Act Premits:

*Secret FBI and Police searches

of your home and office

*Secret government wiretaps on your phone, computer and/ or Internet activity

*Secret

investigations of you bank records, credit cards, and other financial records

*Secret investigations of your library

and book activities

*Secret examinations of your medical records

*The freezing of funds and assests without

prior notice or appeal

*The creation of secret "watch list" that ban those named from air and other travel

Membership Cards

AAA

|

|

|

Birmingham, Alabama, and the Civil Rights

Movement

in 1963

The 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing

The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was used as a meeting-place for civil rights leaders such as Martin

Luther King, Ralph David Abernathy and Fred Shutterworth. Tensions became high when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

(SCLC) and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) became involved in a campaign to register African American to vote in Birmingham. The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was used as a meeting-place for civil rights leaders such as Martin

Luther King, Ralph David Abernathy and Fred Shutterworth. Tensions became high when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

(SCLC) and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) became involved in a campaign to register African American to vote in Birmingham.

On Sunday, 15th September, 1963, a white man was seen getting out of a white and turquoise Chevrolet car and

placing a box under the steps of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Soon afterwards, at 10.22 a.m., the bomb exploded killing

Denise McNair (11), Addie Mae Collins (14), Carole Robertson (14) and Cynthia Wesley (14). The four girls had been attending

Sunday school classes at the church. Twenty-three other people were also hurt by the blast.

Civil rights activists blamed George Wallace, the Governor of Alabama, for the killings. Only a week before

the bombing he had told the New York Times that to stop integration Alabama needed a "few first-class funerals."

A witness identified Robert Chambliss, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, as the man who placed the bomb under the

steps of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. He was arrested and charged with murder and possessing a box of 122 sticks of

dynamite without a permit. On 8th October, 1963, Chambliss was found not guilty of murder and received a hundred-dollar fine

and a six-month jail sentence for having the dynamite.

The case was unsolved until Bill Baxley was elected attorney general of Alabama. He requested the original Federal

Bureau of Investigation files on the case and discovered that the organization had accumulated a great deal of evidence against

Chambliss that had not been used in the original trial.

In November, 1977 Chambliss was tried once again for the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing. Now aged 73,

Chambliss was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. Chambliss died in an Alabama prison on 29th October, 1985.

On 17th May, 2000, the FBI announced that the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing had been carried out by

the Ku Klux Klan splinter group, the Cahaba Boys. It was claimed that four men, Robert Chambliss, Herman Cash, Thomas Blanton

and Bobby Cherry had been responsible for the crime. Cash was dead but Blanton and Cherry were arrested and Blanton has since

been tried and convicted.

Source

Timothy B. Tyson

|

Police use dogs to quell civil unrest in Birmingham, Ala. in May of 1963. Birmingham's police commissioner

"Bull" Connor also allowed firehoses to be turned on young civil rights demonstrators.

Photo Source: The Seattle Times Online

|

Haven to the South's most violent Ku Klux Klan chapter, Birmingham was probably

the most segregated city in the country. Dozens of unsolved bombings and police killings had terrorized the black community

since World War II. Yet King foresaw that "the vulnerability of Birmingham at the cash register would provide the leverage

to gain a breakthrough in the toughest city in the South."

Wyatt Tee Walker, who planned the crusade, said that before Birmingham "we had been trying to win the hearts of white Southerners,

and that was a mistake, a misjudgement. We realized that you have to hit them in the pocket." Birmingham offered the perfect

adversary in Public Safety Commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor, who provided dramatic brutality for an international audience.

SCLC’s [Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a civil rights organization founded in 1957] goal was to create a

political morality play so compelling that the Kennedv administration would be forced to intervene: "The key to everything,"

King observed, "is federal commitment."

The movement initially found it hard to recruit supporters, with black citizens reluctant and Birmingham police restrained.

Slapped with an injunction to cease the demonstrations, King decided to go to jail himself. During his confinement, King penned

"Letter from Birmingham Jail," an eloquent critique of "the white moderate who is more devoted to 'order' than to justice"

and a work included in many composition and literature courses.

The breakthrough came when SCLC’s James Bevel organized thousands of black school children to march in Birmingham.

Police used school buses to arrest hundreds of children who poured into the streets each day. Lacking jail space, "Bull" Connor

used dogs and firehoses to disperse the crowds. Images of vicious dogs and police brutality emblazoned front pages and television

screens around the world. As in Montgomery, King grasped the international implications of SCLC’s strategy. The nation

was 'battling for the minds and the hearts of men in Asia and Africa," he said, "and they aren't gonna respect the United

States of America if she deprives men and women of the basic rights of life because of the color of their skin."

President Kennedy lobbied Birmingham's white business community to reach an agreement. On 10 May local white business leaders

consented to desegregate public facilities, but the details of the accord mattered less than the symbolic triumph. Kennedy

pledged to preserve this mediated halt to "a spectacle which was seriously damaging the reputation of both Birmingham and

the country."

The next day, however, bombs exploded at King's headquarters and at his brother’s home. Violent uprisings followed,

as poor

|

In Birmingham, anti-segregation demonstrators lie on the sidewalk to protect themselves from firemen with

high pressure water hoses. One disgusted fireman said later, "We're supposed to fight fires, not people."

Photo: © Charles Moore

Online Source: www.kodak.com

|

blacks who had little commitment to nonviolence ravaged nine blocks of Birmingham. Rocks and bottles rained on Alabama

state troopers who attacked black citizens in the streets. The violence threatened to mar SCLC’s victory but also helped

cement White House support for civil rights. President Kennedy feared that black Southerners might become "uncontrollable"

if reforms were not negotiated. It was one of the enduring ironies of the civil fights movement that the threat of violence

was so critical to the success of nonviolence.

Across the South, the triumph in Birmingham inspired similar campaigns; in a ten-week period, at least 758 racial demonstrations

in 186 cities sparked 14,733 arrests. Eager to compete with SCLC, the national NAACP pressed Medgar Evers to launch demonstrations

in Jackson, Mississippi, On 11 June President Kennedy made a historic address on national television, describing civil rights

as "a moral issue" and endorsing federal civil rights legislation. Later that night, a member of the White Citizen’s

Council assassinated Medgar Evers.

Tragedy and triumph marked the summer of 1963. As A. Philip Randolph sought to fulfill his vision of a march on the capitol

for jobs, King convinced him to shift the focus to civil rights. Joining with leaders from SCLC, SNCC, the Urban League, and

the NAACP, Randolph chose Bayard Rustin as march organizer. Kennedy endorsed the march, hoping to gain support for the pending

civil rights bill. On 28 August about 250,000 rallied in the most memorable mass demonstration in American history. King's

"I Have a Dream" oration would endure as a historical emblem of nonviolent direct action. Prominent in the crowd was writer

James Baldwin, widely regarded as a black spokesperson, especially since the 1962 publication of his influential work, The

Fire Next Time. Malcolm X’s denunciation of the event as the "farce on Washington" and sharp differences

over the censorship of a speech by SNCC’s John Lewis would later seem to foreshadow the fragmentation of the movement.

But against the lengthening shadow of political violence and racial division--the dynamite murder of four black children at

the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham two weeks later and the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22--the

march gleamed as the apex of interracial liberalism. Toni Morrison used the bombing of the church as part of the rationale

for her characters forming a black vigilante group in Song of Solomon.

From The Oxford Companion to African American Literature. Copyright © 1997 by Oxford University Press.

Profiles of the victims

Addie Mae Collins

Addie Mae Collins and two of her sisters would go door to door every day after school, selling their mother's handmade

cotton aprons and potholders.

The trio collected 35 cents for potholders and 50 cents for aprons. The bibbed aprons netted 75 cents.

"Addie liked to do it. She looked forward to it," said sister Sarah, now Sarah Rudolph. "We sold a lot of them."

When she wasn't selling her mother's wares, Addie liked to play hopscotch, sing in the church choir, draw portraits, and

wear bright colors.

The Hill Elementary School eighth-grader loved to pitch while playing ball, too. "I remember that underhand," said older

sister Janie, now Janie Gaines.

She also remembers Addie's spirit. "She wasn't a shy or timid person. Addie was a courageous person."

Addie, born April 18, 1949, was the seventh of eight children born to Oscar and Alice Collins. When disagreements erupted

among the siblings inside the home on Sixth Court West, Addie was the peacemaker.

"She just always wanted us to love one another and treat each other right," Mrs. Rudolph said. "She was a happy person

also, and she loved life."

The routine was the same every Saturday night at the Collins household - starching Sunday dresses for church. Sept. 14,

1963, was no different when Addie pulled out a white dress. Older sister Flora pressed and curled Addie's short hair.

"We thought it looked pretty on her," said Mrs. Gaines.

When Addie died in the explosion, Mrs. Rudolph lost her right eye. "I feel like I lost my best friend," said Mrs. Rudolph.

"We were always going places together."

Four broken columns in Birmingham's downtown Kelly Ingram Park and the nook in the basement of Sixteenth Street Baptist

Church are both memorials to the four girls killed in the 1963 church bombing.

For 29-year-old Sonya Jones, that is not enough. In January, she renamed her 1-year-old youth center in memory of an aunt

she never knew.

Every second and third Saturday, children file into the Addie Mae Collins Youth Center in an Ishkooda Road church to build

positive attitudes, develop talents and learn to deal with adversity.

"Not only will it be a memorial to her but also we'll be helping other kids who are dealing with tragedies," said Mrs.

Jones, whose mother is Janie Gaines.

Cynthia Wesley

There were times when Cynthia Wesley's father came home weary after a night of patrolling his Smithfield neighborhood for

would-be mischief-makers. Or worse, bombers.

Claude A. Wesley was one of several men who volunteered to ensure another peaceful night on Dynamite Hill, nicknamed for

the frequent and unsolved bombings in a former white neighborhood that was increasingly a home to blacks.

The Wesleys tried to protect their daughter from segregation's brutality.

"We were extremely naive," remembers friend and playmate Karen Floyd Savage. "We didn't really discuss things in depth

like that."

The first adopted daughter of Claude and Gertrude Wesley, Cynthia was a petite girl with a narrow face and size 2 dress.

Cynthia's mother made her clothes, which fit her thin frame perfectly.

She attended the now-defunct Ullman High School, where she did well in math, reading and the band. She invited friends

to parties in her back yard, playing soulful tunes and serving refreshments. She was born April 30, 1949.

"Cynthia was just full of fun all the time," Mrs. Savage said. "We were constantly laughing."

It was while the two girls attended Wilkerson Elementary School that Cynthia traded her gold-band ring topped with a clear,

rectangular stone for a 1954 class ring that belonged to Mrs. Savage.

"We just sort of liked each others' rings and we just traded with no question of wanting it back," Mrs. Savage said.

Cynthia made friends easily, talking often to close pal Rickey Powell. On Sept. 14, 1963, she invited Rickey to church

the next day for a Sunday youth program. Powell accepted, only to reluctantly decline when his mother wanted him to accompany

her to a funeral.

"We were like peas in a pod," Powell said. "That was my best bud."

When Cynthia died in the church blast, she was still wearing the ring Mrs. Savage gave her when they were younger. Cynthia's

father identified her by that ring when he went to the morgue.

The death of the four girls crushed Mrs. Savage.

"I was so young. I never realized someone would hate you so much that they would go to that extent. In a way, that was

sort of the death of my own innocence."

Denise McNair

Denise McNair liked her dolls, left mudpies in the mailbox for childhood crushes and organized a neighborhood fund-raiser

to fight muscular dystrophy.

Born Nov. 17, 1951, Carol Denise McNair was the first child of Chris and Maxine McNair. Her playmates called her Niecie.

A pupil at Center Street Elementary School, she had a knack of gathering neighborhood children to play on the block. She

held tea parties, belonged to the Brownies and played baseball.

"Everybody liked her even if they didn't like each other,"said childhood friend Rhonda Nunn Thomas. "She could play with

anybody."

She and Rhonda would dream of husbands, children and careers. "At one point I would be delivering babies and she was going

to be the pediatrician,"Mrs. Thomas said.

At some point in her young life, Denise asked the neighborhood children to put on skits and dance routines and to read

poetry in a big production to raise money for muscular dystrophy. It became an annual event. People gathered in the yard to

watch the show in Denise's carport — the main stage. Children donated their pennies, dimes and nickels. Adults gave

larger sums.

The muscular dystrophy fund-raiser was always Denise's project — one that nobody refused.

"It was the idea we were doing something special for some kids,"Mrs. Thomas said. "How could you turn it down?"

A relative always thought the girl with the thick, shoulder-length hair and sparkling eyes would be a teacher because she

was "a leader from the heart."

Friend and retired dentist Florita Jamison Askew remembers Denise as a child who smiled a lot, even for the camera when

she lost her baby teeth.

"She was always a ham,"Mrs. Askew said.

"I bet she would have been a real go-getter. She and Carole (Robertson) both. I just wonder sometimes."

Carole Robertson

Smithfield Recreation Center's auditorium became a dance school every Saturday afternoon when eager girls arrived for lessons

in tap, ballet and modern jazz.

Carole Robertson, wearing a leotard and toting black patent leather tap shoes and pink ballet slippers, was among the crowd.

"We didn't have any problems getting our chores done so we could get to dancing class on Saturdays,"said Florita Jamison

Askew, who attended classes with Carole and Carole's big sister."Nobody ever wanted to miss them."

Students worked hard on their ballet and shuffle steps in preparation for the annual spring recital, where they got to

wear makeup and dance with their hair down."It was a lot of fun,"Mrs. Askew said.

Born April 24, 1949, Carole was the third child of Alpha and Alvin Robertson. Older siblings were Dianne and Alvin.

Carole was an avid reader and straight-A student who belonged to Jack and Jill of America, the Girl Scouts, the Parker

High School marching band and science club. She also had attended Wilkerson Elementary School, where she sang in the choir.

Carole walked fast and with a smile.

"She moved through the halls rapidly, not running, but just full of life,"said retired Birmingham teacher Lottie Palmer,

who was a science club sponsor."She was a girl that was anxious to .¤.¤. succeed and do well.

Carole grew up in a Smithfield home that was full of love, friends and the aroma of good cooking, especially her mother's

spaghetti.

"There was a lot of warmth in the house. The food was good and the people were kind," Mrs. Askew said."That was kind of

my second home."

Inside the one-story home with the wrap-around porch, Mrs. Askew and the Robertson girls practiced dances such as the cha-cha

and tried out different hairstyles — often on Carole, who didn't mind being the model.

Carole once told Mrs. Askew, now a retired dentist, about her desire to preserve the past.

"I remember a statement she made — she wanted to teach history or do something his torical. I thought how ironic

it was that she would remain a part of history forever."

In 1976, Chicago residents established the Carole Robertson Center for Learning, a social service agency that serves children

and their families. Named after Carole, it is dedicated to the memory of all four girls.

Members of the Jack and Jill choir were scheduled to sing at Carole's funeral Sept. 17, 1963, at St. John AME Church."Of

course, we didn't do much singing,"said choir member Karen Floyd Savage."We cried through it."

by Chanda Temple © The Birmingham News. Online Source

| African American Scientists |

Benjamin Banneker

(1731-1806) |

Born into a family of free blacks in Maryland, Banneker learned the rudiments of reading, writing, and arithmetic from

his grandmother and a Quaker schoolmaster. Later he taught himself advanced mathematics and astronomy. He is best known for publishing an almanac based on his astronomical calculations. |

Rebecca Cole

(1846-1922) |

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Cole was the second black woman to graduate from medical school (1867). She joined

Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, the first white woman physician, in New York and taught hygiene and childcare to families in poor

neighborhoods. |

Edward Alexander Bouchet

(1852-1918) |

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Bouchet was the first African American to graduate (1874) from Yale College. In 1876,

upon receiving his Ph.D. in physics from Yale, he became the first African American to earn a doctorate. Bouchet spent his

career teaching college chemistry and physics. |

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams

(1856-1931) |

Williams was born in Pennsylvania and attended medical school in Chicago, where he received his M.D. in 1883. He founded

the Provident Hospital in Chicago in 1891, and he performed the first successful open heart surgery in 1893. |

George Washington Carver

(1865?-1943) |

Born into slavery in Missouri, Carver later earned degrees from Iowa Agricultural College. The director of agricultural

research at the Tuskegee Institute from 1896 until his death, Carver developed hundreds of applications for farm products important to the economy of the South,

including the peanut, sweet potato, soybean, and pecan. |

Charles Henry Turner

(1867-1923) |

A native of Cincinnati, Ohio, Turner received a B.S. (1891) and M.S. (1892) from the University of Cincinnati and a Ph.D.

(1907) from the University of Chicago. A noted authority on the behavior of insects, he was the first researcher to prove

that insects can hear. |

Ernest Everett Just

(1883-1941) |

Originally from Charleston, South Carolina, Just attended Dartmouth College and the University of Chicago, where he earned

a Ph.D. in zoology in 1916. Just's work on cell biology took him to marine laboratories in the U.S. and Europe and led him

to publish more than 50 papers. |

Archibald Alexander

(1888-1958) |

Iowa-born Alexander attended Iowa State University and earned a civil engineering degree in 1912. While working for an

engineering firm, he designed the Tidal Basin Bridge in Washington, D.C. Later he formed his own company, designing Whitehurst

Freeway in Washington, D.C. and an airfield in Tuskegee, Alabama, among other projects. |

Roger Arliner Young

(1889-1964) |

Ms. Young was born in Virginia and attended Howard University, University of Chicago, and University of Pennsylvania,

where she earned a Ph.D. in zoology in 1940. Working with her mentor, Ernest E. Just, she published a number of important

studies. |

Dr. Charles Richard Drew

(1904-1950) |

Born in Washington, D.C., Drew earned advanced degrees in medicine and surgery from McGill University in Montreal, Quebec,

in 1933 and from Columbia University in 1940. He is particularly noted for his research in blood plasma and for setting up

the first blood bank. |

| African American Inventors |

Thomas L. Jennings

(1791-1859) |

A tailor in New York City, Jennings is credited with being the first African American to hold a U.S. patent. The patent,

which was issued in 1821, was for a dry-cleaning process. |

Norbert Rillieux

(1806-1894) |

Born the son of a French planter and a slave in New Orleans, Rillieux was educated in France. Returning to the U.S., he

developed an evaporator for refining sugar, which he patented in 1846. Rillieux's evaporation technique is still used in the

sugar industry and in the manufacture of soap and other products. |

Benjamin Bradley

(1830?-?) |

A slave, Bradley was employed at a printing office and later at the Annapolis Naval Academy, where he helped set up scientific

experiments. In the 1840s he developed a steam engine for a war ship. Unable to patent his work, he sold it and with the proceeds

purchased his freedom. |

Elijah McCoy

(1844-1929) |

The son of escaped slaves from Kentucky, McCoy was born in Canada and educated in Scotland. Settling in Detroit, Michigan,

he invented a lubricator for steam engines (patented 1872) and established his own manufacturing company. During his lifetime

he acquired 57 patents. |

Lewis Howard Latimer

(1848-1929) |

Born in Chelsea, Mass., Latimer learned mechanical drawing while working for a Boston patent attorney. He later invented

an electric lamp and a carbon filament for light bulbs (patented 1881, 1882). Latimer was the only African-American member

of Thomas Edison's engineering laboratory. |

Granville T. Woods

(1856-1910) |

Woods was born in Columbus, Ohio, and later settled in Cincinnati. Largely self-educated, he was awarded more than 60

patents. One of his most important inventions was a telegraph that allowed moving trains to communicate with other trains

and train stations, thus improving railway efficiency and safety. |

Madame C.J. Walker

(1867-1919) |

Widowed at 20, Louisiana-born Sarah Breedlove Walker supported herself and her daughter as a washerwoman. In the early

1900s she developed a hair care system and other beauty products. Her business, headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana, amassed

a fortune, and she became a generous patron of many black charities. |

Garrett Augustus Morgan

(1877-1963) |

Born in Kentucky, Morgan invented a gas mask (patented 1914) that was used to protect soldiers from chlorine fumes during

World War I. Morgan also received a patent (1923) for a traffic signal that featured automated STOP and GO signs. Morgan's

invention was later replaced by traffic lights. |

Frederick McKinley Jones

(1892-1961) |

Jones was born in Cincinnati, Ohio. An experienced mechanic, he invented a self-starting gas engine and a series of devices

for movie projectors. More importantly, he invented the first automatic refrigeration system for long-haul trucks (1935).

Jones was awarded more than 40 patents in the field of refrigeration. |

David Crosthwait, Jr.

(1898-1976) |

Born in Nashville, Tennessee, Crosthwait earned a B.S. (1913) and M.S. (1920) from Purdue University. An expert on heating,

ventilation, and air conditioning, he designed the heating system for Radio City Music Hall in New York. During his lifetime

he received some 40 U.S. patents relating to HVAC systems. |

Africa is not only the original home of humanity, it is the cradle of its intellect. It was on Africa's savannahs, riverbanks,

highlands, deserts, and forests that the first men and women used the power of their minds to shape their environment in ways

that suited them. Here man established himself as a tool maker and hunter and advanced social animal. Over the course of millions

of years, groups of prehistoric Africans of the genus Homo reasoned, judged, understood, and created the basis for much of

the technology and industry that exists in the world today. John E. Pfeiffer. Africa is not only the original home of humanity, it is the cradle of its intellect. It was on Africa's savannahs, riverbanks,

highlands, deserts, and forests that the first men and women used the power of their minds to shape their environment in ways

that suited them. Here man established himself as a tool maker and hunter and advanced social animal. Over the course of millions

of years, groups of prehistoric Africans of the genus Homo reasoned, judged, understood, and created the basis for much of

the technology and industry that exists in the world today. John E. Pfeiffer.

BUY THE BOOK. For more Books Click here.... . .

Take a shot at the BLACK INVENTORS QUIZ Submit a Black Inventor HERE

Contemporary Black Inventors

|

1 |

A.P. Abourne |

Refining of coconut oil. |

July 27, 1980 |

|

2 |

A. B. Blackburn |

Spring seat for chairs. Patent# 380,420 |

April 3, 1888 |

|

3 |

A.C. Richardson |

Casket-Lowering Device. Patent# 529,311 |

November 13, 1894 |

|

4 |

A.C. Richardson |

Churn. Patent # 466,470 |

February 17, 1891 |

|

5 |

A.E. Long and A.A. Jones-- |

Caps For Bottles And Jars |

1898 |

|

6 |

A.L. Lewis |

Window Cleaner |

1892 |

|

7 |

A.L. Rickman |

Galoshes |

1898 |

|

8 |

Anna M. Mangin |

Pastry fork |

March 1, 1892 |

|

9 |

Alexander P. Ashbourne |

Biscuit Cutter |

November, 1875 |

|

10 |

Alexander Miles |

Elevator and also safety device for elevators. Patent No. 371,207 |

October11, 1887 |

|

11 |

Alfred L. Cralle |

Ice Cream Scooper. Patent # 576,395 |

February 2,1897 |

|

12 |

Alice Parker |

Heating Furnace |

1918 |

|

13 |

Andrew Beard |

Automatic Car Coupling Device |

1897 |

|

14 |

Augustus Jackson |

Ice cream |

1832 |

|

15 |

B. F. Cargill |

Invalid cot. Patent# 629,658 |

July 25, 1899 |

|

16 |

B.F. Jackson |

Gas Burner |

|

|

17 |

Benjamin Banneker |

Clock, Prints for Wash. DC 1st Almanac |

|

|

18 |

Bessie V. Griffin |

Portable Receptacle |

1951 |

|

19 |

C.B. Brook |

Street Sweeper |

1896 |

|

20 |

C.V. Richey |

Fire Escape Bracket. Patent # 596,427 |

December 28, 1897 |

|

21 |

C. W. Allen |

Self Leveling table. Patent # 613,436 |

November 1, 1898 |

|

22 |

D. McCree |

Portable Fire Escape. Patent # 440,322 |

November 11, 1890 |

|

23 |

Darryl Thomas |

Cattle Roping Apparatus |

|

|

24 |

Dr. Charles Drew |

Invented Blood Banks And Established Them Around The World |

1940 |

|

25 |

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams |

Performed First Open Heart Surgery |

1893 |

|

26 |

Edmond Berger |

Spark Plug |

|

|

27 |

Elbert R. Robinson |

Electric Railway Trolley |

|

|

28 |

Ellen Elgin |

Clothes Wringer |

1880s |

|

29 |

Elijah Mccoy |

Automatic Lubrication System (For Railroad And Heavy Machinery) 1892 |

July 2, 1872 |

|

30 |

Folarin Sosan |

Package-Park (Solves Package Delivery Dilemma) www.maita.com |

1997 |

|

31 |

Frederick Jones |

Ticket Dispensing Machine. Patent # 2163754 |

June 27, 1939 |

|

32 |

Frederick Jones |

Starter Generator. Patent # 2475842 |

July 12, 1949 |

|

33 |

Frederick Jones |

Two-Cycle gasoline Engine. Patent # 2523273 |

November 28, 1950 |

|

34 |

Frederick Jones |

Air Condition. Patent # 2475841 |

July 12, 1949 |

|

35 |

Frederick Jones |

Portable X-Ray Machine |

|

|

36 |

G.W. Murray |

Cultivator and Marker. Patent # 517,961 |

April 10, 1894 |

|

37 |

G.W. Murray |

Combined Furrow Opener and Stalk-Knocker. Patent # 517,960 |

April 10, 1894 |

|

38 |

G.W. Murray |

Fertilizer Distributor. Patent# 520,889 |

June 5, 1894 |

|

39 |

G.W. Murray |

Cotton Chopper. Patent # 520,888 |

June 5, 1894 |

|

40 |

G.W. Murray |

Planter. Patent # 520,887 |

June 5, 1894 |

|

41 |

G. F. Grant |

Golf Tee. Patent # 638,920 |

December 12, 1899 |

|

42 |

G.T. Sampson |

Clothes Drier |

1892 |

|

43 |

G.W. Kelley |

Steam Table |

1897 |

|

44 |

Garret A. Morgan |

Gas Mask (Saved Many Lives During WWI) |

1914 |

|

45 |

George Alcorn |

Fabrication of spectrometer. Patent # 4,618,380 |

October 21, 1986 |

|

46 |

George Tolivar |

Ship's propeller |

|

|

47 |

George Washington Carver |

Peanut Butter |

1900 |

|

48 |

George Washington Carver |

300 products from peanuts, 118 products from the sweet potato and 75 from the pecan. |

1900-1943 |

|

49 |

Garret A. Morgan |

Automatic Traffic Signal |

1923 |

|

50 |

Gertrude E. Downing and William Desjardin |

Corner Cleaner Attachment.

Patent # 3,715,772 |

February 13, 1973 |

|

51 |

Granville Woods |

Telephone (His Telephone Was Far Superior To Alexander Graham Bell's) |

Dec. 2,1884 |

|

52 |

Granville Woods |

Trolley Car |

1888 |

|

53 |

Granville Woods |

Multiplex Telegraph System (Allowed Messages To Be Sent And Received From Moving Trains) |

1887 |

|

54 |

Granville Woods |

Railway Air Brakes (The First Safe Method Of Stopping Trains) 1903 |

|

|

55 |

Granville Woods |

Steam Boiler/Radiator |

1884 |

|

56 |

Granville Woods-- |

Third Rail (Subway) |

|

|

57 |

H. Grenon |

Razor Stropping Device. Patent # 554,867 |

February 18, 1896 |

|

58 |

H.H. Reynolds |

Window Ventilator for Railroad Cars.

Patent No.275,271 |

April 3, 1883 |

|

59 |

H.A. Jackson |

Kitchen Table |

|

|

60 |

Henry Blair |

Mechanical Seed Planter |

1830 |

|

61 |

Henry Blair |

Mechanical Corn Harvester |

|

|

62 |

Henry Single |

Patented an Improved Fish Hook. He sold it later for $625. |

1854 |

|

63 |

Henry Sampson |

Cellular Phone |

July 6th, 1971 |

|

64 |

I.O. Carter |

Nursery Chair |

1960 |

|

65 |

Issac R. Johnson |

Bicycle Frame |

|

|

66 |

J. A. Joyce |

Ore Bucket. Patent # 603,143 |

April 26, 1898 |

|

67 |

J. Hawkins |

Patented the Gridiron |

March 3, 1845 |

|

68 |

J. Gregory |

Motor |

|

|

69 |

J.A. Sweeting |

Cigarette Roller |

1897 |

|

70 |

J.B. Winters |

Fire Escape Ladder |

|

|

71 |

J. H. Hunter |

Portable Weighing Scales. Patent # 570,533 |

November 3, 1896 |

|

72 |

J.F. Pickering |

Air Ship |

1892 |

|

73 |

J. H. Robinson |

Lifesaving guards for Street Cars. Patent# 623,929 |

April 25, 1899 |

|

74 |

J. Robinson |

Dinner Pail. Patent# 356,852 |

February 1, 1887 |

|

75 |

J. W. Reed |

Dough Kneader and Roller. Patents# 304,552 |

September 2, 1884 |

|

76 |

J. Ross |

Bailing Press. Patent # 632,539 |

Sept 05, 1899 |

|

77 |

J.H. White |

Convertible Sette (A Large Sofa) |

1892 |

|

78 |

J.H. White |

Lemon Squeezer |

1896 |

|

79 |

J.L. Love |

Pencil Sharpener. Patent # 594,114 |

23 November 1897 |

|

80 |

J.S. Smith |

Lawn Sprinkler. Patent # 581,785 |

May 4, 1897 |

|

81 |

James Forten |

Sailing Apparatus |

1850 |

|

82 |

James S. Adams |

Airplane Propelling |

|

|

83 |

Jan Matzelinger |

Automatic Shoe Making Machine |

1883 |

|

84 |

Joan Clark |

Medicine Tray |

1987 |

|

85 |

John A. Johnson |

Wrench |

|

|

86 |

John Burr |

Lawn Mower |

|

|

87 |

John Parker |

"Parker Pulverizer" Follower-Screw for Tobacco Presses. Patent# 304,552 |

September 2, 1884 |

|

88 |

John Standard |

Refrigerator. Patent# 304,552 |

Jul 14,1894 |

|

89 |

Joseph Gammel |

Supercharge System for Internal Combustion Engine |

|

|

90 |

Joseph N. Jackson |

Programmable Remote Control |

|

|

91 |

L.C. Bailey |

Folding Bed |

1899 |

|

92 |

L. Bell |

Locomotive smoke stack. Patent# 115,153 |

May 23, 1871 |

|

93 |

L. F. Brown |

Bridle bit. Patent # 484,994 |

October 25, 1892 |

|

94 |

L.S. Burridge And N.R. Marsham |

Typewriter |

1885 |

|

95 |

Lewis Howard Latimer |

Light Bulb Filament |

|

|

96 |

Lewis Temple |

Toggle Harpoon (Revolutionized The Whaling Industry) |

1848 |

|

97 |

Lloyd A. Hall |

Chemical compound to preserve meat |

|

|

98 |

Lloyd P. Ray |

Dust Pan |

|

|

99 |

Lydia Holmes |

Wood Toys. Patent # 2,529,692 |

November 14, 1950 |

|

100 |

Lydia O. Newman |

Hair brush |

|

|

101 |

M.C. Harney |

Lantern/Lamp |

Aug.19, 1884 |

|

102 |

Madam. C. Walker |

Hair Care Products |

1905 |

|

103 |

Majorie Joyner |

Permanent hair wave machine. Patent # 1693515 |

November 27, 1928 |

|

104 |

Madeline M. Turner |

The Fruit Press |

1916 |

|

105 |

Marie V. Brittan Brown |

Security System. Patent # 3,482,037 |

December 2, 1969 |

|

106 |

Manley West |

Discovered compound in canibis to cure glaucoma. |

1980-1987 |

|

107 |

Norbett Rillieux |

Sugar Refining System |

1846 |

|

108 |

O.B. Clare |

Rail Tresle. Patent# 390,753 |

October 9, 1888 |

|

109 |

O. E. Brown |

Horse Shoe |

8/23/1892 |

|

110 |

Onesimus |

Small Pox Inoculation (He Brought This Method From Africa Where Advance Medical Practices Were In Use Long Before

Europeans Had Any Medical Knowledge) |

1721 |

|

111 |

Otis F. Boykin |

Wire Type Precision Resistor.

Patent # U.S. 2,891,227 |

June 16, 1959 |

|

112 |

Paul E Williams |

Helicopter |

|

|

113 |

Peter Walker |

Machine for Cleaning Seed Cotton |

|

|

114 |

Phillip Downing |

Letter Drop Mailbox. Patent # 462,096 |

October 27, 1891 |

|

115 |

Philip Emeagwali |

Accurate Weather Forecasting |

1990 |

|

116 |

Philip Emeagwali |

Hyperball Computer |

April 1996 |

|

117 |

Philip Emeagwali |

Improved Petroleum Recovery |

1990 |

|

118 |

Philip Emeagwali |

World's Fastest Computer |

1989 |

|

119 |

R.A. Butler |

Train alarm. Patent #157,370 |

June 15, 1897 |

|

120 |

R.P. Scott |

Corn Silker |

1894 |

|

121 |

Richard Spikes |

Automatic Gear Shift |

|

|

122 |

Robert Flemming Jr. |

Guitar |

March 3, 1886 |

|

123 |

S. H. Love |

Improvement to military guns. Patent # 1301143. |

22 April 1919 |

|

124 |

S. H. Love |

Improve Vending Machine. Patent # 1936515 |

November 21, 1933 |

|

125 |

Sara E. Goode |

Cabinet Bed |

1885 |

|

126 |

Rufus Stokes Patent #3,378,241 |

Exhaust Purifier |

April 16, 1968 |

|

127 |

Sarah Boone |

Ironing Board |

April 26, 1892 |

|

128 |

T. Elkins |

Toilet |

1897 |

|

129 |

T. J. Byrd |

Rail car coupling . Patent# 157,370 |

December 1, 1874 |

|

130 |

Thomas Carrington |

Range Oven |

1876 |

|

131 |

Thomas J.Martin |

Patented the Fire Extinguisher |

March 26, 1872 |

|

132 |

Thomas W. Stewart |

Mop |

1893 |

|

133 |

Virgie M. Ammons |

Fireplace Damper Actuating Tool. Patent # 3,908,633 |

September 30, 1975 |

|

134 |

W. A. Lovette |

The Advance Printing Press |

|

|

135 |

W. F. Burr |

Railway Switching device . Patent # 636,197 |

Oct.31,1899 |

|

136 |

W. H. Ballow |

Combined hatrack and table. Patent # 601,422 |

March 29, 1898 |

|

137 |

W.S. Campbell |

Self-setting animal trap. Patent# 246,369 |

August 30, 1881 |

|

138 |

W. Johnson |

Egg Beater |

1884 |

|

139 |

W.B. Purvis |

The Fountain Pen Patent# 419,065 |

Jan 7,1890 |

|

140 |

W.D. Davis |

Riding Saddles |

October 6, 1895 |

|

141 |

W.H. Sammons |

Hot Comb |

1920 |

|

142 |

W.S. Grant |

Curtain Rod Support |

1896 |

|

143 |

William Barry |

Postmarking and Canceling machine |

|

|

144 |

Wm. Harwell |

Attachment for shuttle arm; device used to capture satellites |

|

Fun Links

How about some jokes?

Play a game!

|

|

|

|

Information on Our Organization

Globetrotters

Travel Planning

Malcolm X's Eulogy

Eulogy delivered by Ossie Davis at the funeral

of Malcolm X

Faith Temple Church Of God

February 27,1965

"Here - at this

final hour, in this quiet place - Harlem has come to bid farewell to one of its brightest hopes -extinguished now, and gone

from us forever. For Harlem is where he worked and where he struggled and fought - his home of homes, where his heart was,

and where his people are - and it is, therefore, most fitting that we meet once again - in Harlem - to share these last moments

with him. For Harlem has ever been gracious to those who have loved her, have fought her, and have defended her honor even

to the death.

It is not in the memory of man that this beleaguered, unfortunate, but nonetheless proud community has

found a braver, more gallant young champion than this Afro-American who lies before us - unconquered still. I say the word

again, as he would want me to : Afro-American - Afro-American Malcolm, who was a master, was most meticulous in his use of

words. Nobody knew better than he the power words have over minds of men. Malcolm had stopped being a 'Negro' years ago. It

had become too small, too puny, too weak a word for him. Malcolm was bigger than that. Malcolm had become an Afro-American

and he wanted - so desperately - that we, that all his people, would become Afro-Americans too.

There are those who

will consider it their duty, as friends of the Negro people, to tell us to revile him, to flee, even from the presence of

his memory, to save ourselves by writing him out of the history of our turbulent times. Many will ask what Harlem finds to

honor in this stormy, controversial and bold young captain - and we will smile. Many will say turn away - away from this man,

for he is not a man but a demon, a monster, a subverter and an enemy of the black man - and we will smile. They will say that

he is of hate - a fanatic, a racist - who can only bring evil to the cause for which you struggle! And we will answer and

say to them : Did you ever talk to Brother Malcolm? Did you ever touch him, or have him smile at you? Did you ever really

listen to him? Did he ever do a mean thing? Was he ever himself associated with violence or any public disturbance? For if

you did you would know him. And if you knew him you would know why we must honor him.

Malcolm was our manhood, our

living, black manhood! This was his meaning to his people. And, in honoring him, we honor the best in ourselves. Last year,

from Africa, he wrote these words to a friend: 'My journey', he says, 'is almost ended, and I have a much broader scope than

when I started out, which I believe will add new life and dimension to our struggle for freedom and honor and dignity in the

States. I am writing these things so that you will know for a fact the tremendous sympathy and support we have among the African

States for our Human Rights struggle. The main thing is that we keep a United Front wherein our most valuable time and energy

will not be wasted fighting each other.' However we may have differed with him - or with each other about him and his value

as a man - let his going from us serve only to bring us together, now.

Consigning these mortal remains to earth, the

common mother of all, secure in the knowledge that what we place in the ground is no more now a man - but a seed - which,

after the winter of our discontent, will come forth again to meet us. And we will know him then for what he was and is - a

Prince - our own black shining Prince! - who didn't hesitate to die, because he loved us so."

(Eulogy delivered at Comrade George Jackson memorial service August

28,1971)

-Huey P. Newton-

"When I went to prison in 1967, I met George. Not physically, I met him

through his ideas, his thoughts and words that I would get from him. He was at Soledad Prison at the time; I was at California

Penal Colony. George was a legendary figure all through the prison system, where he spent most of his life. You know a legendary

figure is known to most people through the idea, or through the concept, or essentially through the spirit".

"So I met George through the spirit. I say that the legendary figure

is also a hero. He set a standard for prisoners, political prisoners, for people. He showed the love, the strength, the revolutionary

feror that's characteristic of any soldier for the people. So we know that spiritual things can only manifest themselves in

some physical act, through a physical mechanism".

"I saw prisoners who knew about this legendary figure, act in such a

way, putting his ideas to life; so therefore the spirit became a life. And I would like to say today George's body has fallen,

but his spirit goes on, because his ideas live. And we will see that these ideas stay alive, because they'll be manifested

in our bodies and in those young Panther bodies, who are our childern".

" So it's a true saying that there will be revolution from one generation

to the next. What kind of standard did George Jackson set? First, that he was a strong man, he was determind, full of love,

strength, dedication to the people's cause, without fear. He lived the life that we must praise. It was a life, no matter

how he was oppressed, no matter how wrongly he was done, he still kept the love for the people".

"And this is why he felt no pain in giving up his life for the people's

cause. The state sets the stage for the kind of contradiction or violence that occurs in the world, that occurs in the prisons.

The ruling circle of the United States has terrorized the world. The state has the audacity to say they have the right to

kill. They say they have a death penalty and it's legal. But I say by the laws of nature that no death penalty can be legal-it's

only cold-blooded murder".

"It gives spur to all sorts of violence, because every man has a contract

with himself, that he must keep himself alive at all costs. They have the audacity to say that people should deliver a life

to them without a struggle; but none of us can accept that. George Jackson had every right, every right to do everything possible

to perseve his life and the life of his comrades, the life of the People".

"George Jackson, even after his death, you see, is going on living in

a real way; because after all, the greatest thing that we have is the idea and our spirit, because it can be passed on. Not

in the superstitious sense, but in the sense that when we say something or we live a certain way, then when this can be passed

on to anther person, then life goes on. And that person somehow lives, because the standard that he set and the standard that

he lived by will go on living".

"Even with George's last statement-his last statement to me-at

San Quentin that day, that terrible day, he left a standard for political prisoners; he left a standard for the liberation

armies of the world. He showed us how to act..."

(Eulogy delivered at Comrade George Jackson memorial service August

28,1971)

-Huey P. Newton-

Martin Luther King's Eulogy for the Young Victims of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church

Bombing, delivered at Sixth Avenue Baptist Church

18 September 1963

Birmingham, Ala.

[Delivered at funeral service for three of the children—Addie Mae Collins, Carol Denise McNair,

and Cynthia Diane Wesley—killed in the bombing. A separate service was held for the fourth victim, Carole Robertson.]

This afternoon we gather in the quiet of this sanctuary to pay our last tribute of respect

to these beautiful children of God. They entered the stage of history just a few years ago, and in the brief years that they

were privileged to act on this mortal stage, they played their parts exceedingly well. Now the curtain falls; they move through

the exit; the drama of their earthly life comes to a close. They are now committed back to that eternity from which they came.

These children—unoffending, innocent, and beautiful—were the victims of

one of the most vicious and tragic crimes ever perpetrated against humanity.

And yet they died nobly. They are the martyred heroines of a holy crusade for freedom

and human dignity. And so this afternoon in a real sense they have something to say to each of us in their death. They have

something to say to every minister of the gospel who has remained silent behind the safe security of stained-glass windows.

They have something to say to every politician [Audience:] (Yeah) who has fed his constituents with the stale

bread of hatred and the spoiled meat of racism. They have something to say to a federal government that has compromised with

the undemocratic practices of southern Dixiecrats (Yeah) and the blatant hypocrisy of right-wing northern Republicans.

(Speak) They have something to say to every Negro (Yeah) who has passively accepted the evil system of segregation

and who has stood on the sidelines in a mighty struggle for justice. They say to each of us, black and white alike, that we

must substitute courage for caution. They say to us that we must be concerned not merely about who murdered them, but about

the system, the way of life, the philosophy which produced the murderers. Their death says to us that we must work passionately

and unrelentingly for the realization of the American dream.

And so my friends, they did not die in vain. (Yeah) God still has a way of wringing

good out of evil. (Oh yes) And history has proven over and over again that unmerited suffering is redemptive. The innocent

blood of these little girls may well serve as a redemptive force (Yeah) that will bring new light to this dark city.

(Yeah) The holy Scripture says, "A little child shall lead them." (Oh yeah) The death of these little children

may lead our whole Southland (Yeah) from the low road of man's inhumanity to man to the high road of peace and brotherhood.

(Yeah, Yes) These tragic deaths may lead our nation to substitute an aristocracy of character for an aristocracy of

color. The spilled blood of these innocent girls may cause the whole citizenry of Birmingham (Yeah)

to transform the negative extremes of a dark past into the positive extremes of a bright future. Indeed this tragic event

may cause the white South to come to terms with its conscience. (Yeah)

And so I stand here to say this afternoon to all assembled here, that in spite of the

darkness of this hour (Yeah Well), we must not despair. (Yeah, Well) We must not become bitter (Yeah, That’s

right), nor must we harbor the desire to retaliate with violence. No, we must not lose faith in our white brothers. (Yeah,

Yes) Somehow we must believe that the most misguided among them can learn to respect the dignity and the worth of all

human personality.

May I now say a word to you, the members of the bereaved families? It is almost impossible

to say anything that can console you at this difficult hour and remove the deep clouds of disappointment which are floating

in your mental skies. But I hope you can find a little consolation from the universality of this experience. Death comes to

every individual. There is an amazing democracy about death. It is not aristocracy for some of the people, but a democracy

for all of the people. Kings die and beggars die; rich men and poor men die; old people die and young people die. Death comes

to the innocent and it comes to the guilty. Death is the irreducible common denominator of all men.

I hope you can find some consolation from Christianity's affirmation that death is not

the end. Death is not a period that ends the great sentence of life, but a comma that punctuates it to more lofty significance.

Death is not a blind alley that leads the human race into a state of nothingness, but an open door which leads man into life

eternal. Let this daring faith, this great invincible surmise, be your sustaining power during these trying days.

Now I say to you in conclusion, life is hard, at times as hard as crucible steel. It

has its bleak and difficult moments. Like the ever-flowing waters of the river, life has its moments of drought and its moments

of flood. (Yeah, Yes) Like the ever-changing cycle of the seasons, life has the soothing warmth of its summers and

the piercing chill of its winters. (Yeah) And if one will hold on, he will discover that God walks with him (Yeah,

Well), and that God is able (Yeah, Yes) to lift you from the fatigue of despair to the buoyancy of hope, and transform

dark and desolate valleys into sunlit paths of inner peace.

And so today, you do not walk alone. You gave to this world wonderful children. [moans]

They didn’t live long lives, but they lived meaningful lives. (Well) Their lives were distressingly small in

quantity, but glowingly large in quality. (Yeah) And no greater tribute can be paid to you as parents, and no greater

epitaph can come to them as children, than where they died and what they were doing when they died. (Yeah) They did

not die in the dives and dens of Birmingham (Yeah, Well), nor did they die discussing and listening to filthy jokes.

(Yeah) They died between the sacred walls of the church of God (Yeah, Yes), and they were discussing the eternal

meaning (Yes) of love. This stands out as a beautiful, beautiful thing for all generations. (Yes) Shakespeare

had Horatio to say some beautiful words as he stood over the dead body of Hamlet. And today, as I stand over the remains of

these beautiful, darling girls, I paraphrase the words of Shakespeare: (Yeah, Well): Good night, sweet princesses.

Good night, those who symbolize a new day. (Yeah, Yes) And may the flight of angels (That’s right) take

thee to thy eternal rest. God bless you.

Online Source

Civil Rights Timeline

Milestones

in the modern civil rights movement

| by Borgna Brunner and Elissa Haney |

|

| 1954 |

- May 17

- The Supreme Court rules on the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka,

Kans., unanimously agreeing that segregation in public schools is unconstitutional. The ruling paves the way for large-scale desegregation.

The decision overturns the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling that sanctioned "separate but equal" segregation of

the races, ruling that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." It is a victory for NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall, who will later return to the Supreme Court as the nation's first black justice.

|

| 1955 |

- Aug.

- Fourteen-year-old Chicagoan Emmett Till is visiting family in Mississippi when he is kidnapped, brutally beaten, shot, and dumped in the Tallahatchie River for allegedly

whistling at a white woman. Two white men, J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant, are arrested for the murder and acquitted by an all-white

jury. They later boast about committing the murder in a Look magazine interview. The case becomes a cause célèbre

of the civil rights movement.

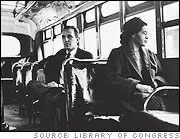

- Dec. 1

- (Montgomery, Ala.) NAACP member Rosa Parks refuses to give up her seat at the front of the "colored section" of a bus to a white passenger, defying a southern custom

of the time. In response to her arrest the Montgomery black community launches a bus boycott, which will last for more than

a year, until the buses are desegregated Dec. 21, 1956. As newly elected president of the Montgomery Improvement Association

(MIA), Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., is instrumental in leading the boycott.

|

| 1957 |

- Jan.–Feb.

- Martin Luther King, Charles K. Steele, and Fred L. Shuttlesworth establish the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, of which King is made the first president. The SCLC becomes a major

force in organizing the civil rights movement and bases its principles on nonviolence and civil disobedience. According to

King, it is essential that the civil rights movement not sink to the level of the racists and hatemongers who oppose them:

"We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline," he urges.

- Sept.

- (Little Rock, Ark.) Formerly all-white Central High School learns that integration is easier said than done. Nine black students are blocked from entering the school on the orders of Governor Orval Faubus. President Eisenhower sends federal troops and the National Guard to intervene on behalf of the students, who become known as the "Little Rock Nine."

|

| 1960 |

- Feb. 1

- (Greensboro, N.C.) Four black students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College begin a sit-in at a segregated Woolworth's lunch counter. Although

they are refused service, they are allowed to stay at the counter. The event triggers many similar nonviolent protests throughout

the South. Six months later the original four protesters are served lunch at the same Woolworth's counter. Student sit-ins

would be effective throughout the Deep South in integrating parks, swimming pools, theaters, libraries, and other public facilities.

- April

- (Raleigh, N.C.) The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) is founded at Shaw University, providing young blacks with a place in the civil rights movement. The SNCC later grows

into a more radical organization, especially under the leadership of Stokely Carmichael (1966–1967).

|

| 1961 |

- May 4

- The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) begins sending student volunteers on bus trips to test the implementation of new laws prohibiting segregation in interstate

travel facilities. One of the first two groups of "freedom riders," as they are called, encounters its first problem two weeks later, when a mob in Alabama sets the riders' bus on fire. The

program continues, and by the end of the summer 1,000 volunteers, black and white, have participated.

- Oct. 1

- James Meredith becomes the first black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi. Violence and riots surrounding the incident cause

President Kennedy to send 5,000 federal troops.

|

| 1963 |

- April 16

- Martin Luther King is arrested and jailed during anti-segregation protests in Birmingham, Ala.; he writes his seminal

"Letter from Birmingham Jail," arguing that individuals have the moral duty to disobey unjust laws.

- May

- During civil rights protests in Birmingham, Ala., Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene "Bull" Connor uses fire hoses and

police dogs on black demonstrators. These images of brutality, which are televised and published widely, are instrumental

in gaining sympathy for the civil rights movement around the world.

- June 12

- (Jackson, Miss.) Mississippi's NAACP field secretary, 37-year-old Medgar Evers, is murdered outside his home. Byron De La Beckwith is tried twice in 1964, both trials resulting in hung juries. Thirty

years later he is convicted for murdering Evers.

- Aug. 28

- (Washington, D.C.) About 200,000 people join the March on Washington. Congregating at the Lincoln Memorial, participants listen as Martin Luther King delivers his famous "I Have a Dream" speech.

- Sept. 15

- (Birmingham, Ala.) Four young girls (Denise McNair, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Addie Mae Collins) attending Sunday school are killed when a bomb explodes at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, a popular location for civil rights meetings. Riots erupt in Birmingham, leading

to the deaths of two more black youths.

|

| 1964 |

- Jan. 23

- The 24th Amendment abolishes the poll tax, which originally had been instituted in 11 southern states after Reconstruction

to make it difficult for poor blacks to vote.

- Summer

- The Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), a network of civil rights groups that includes CORE and SNCC, launches

a massive effort to register black voters during what becomes known as the Freedom Summer. It also sends delegates to the

Democratic National Convention to protest—and attempt to unseat—the official all-white Mississippi contingent.

- July 2

- President Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The most sweeping civil rights legislation since Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination of all kinds

based on race, color, religion, or national origin. The law also provides the federal government with the powers to enforce

desegregation.

- Aug. 4

- (Neshoba Country, Miss.) The bodies of three civil-rights workers—two white, one black—are found in an earthen dam, six weeks into a federal investigation backed by President Johnson. James E. Chaney, 21; Andrew Goodman, 21; and Michael Schwerner, 24, had been working to register black voters in Mississippi,

and, on June 21, had gone to investigate the burning of a black church. They were arrested by the police on speeding charges,

incarcerated for several hours, and then released after dark into the hands of the Ku Klux Klan, who murdered them.

|

| 1965 |

- Feb. 21

- (Harlem, N.Y.) Malcolm X, black nationalist and founder of the Organization of Afro-American Unity, is shot to death. It is believed the assailants

are members of the Black Muslim faith, which Malcolm had recently abandoned in favor of orthodox Islam.

- March 7

- (Selma, Ala.) Blacks begin a march to Montgomery in support of voting rights but are stopped at the Pettus Bridge by a police blockade.

Fifty marchers are hospitalized after police use tear gas, whips, and clubs against them. The incident is dubbed "Bloody Sunday"

by the media. The march is considered the catalyst for pushing through the voting rights act five months later.

- Aug. 10

- Congress passes the Voting Rights Act of 1965, making it easier for Southern blacks to register to vote. Literacy tests,

poll taxes, and other such requirements that were used to restrict black voting are made illegal.

- Aug. 11–17, 1965

- (Watts, Calif.) Race riots erupt in a black section of Los Angeles.

- Sept. 24, 1965

- Asserting that civil rights laws alone are not enough to remedy discrimination, President Johnson issues Executive Order

11246, which enforces affirmative action for the first time. It requires government contractors to "take affirmative action"

toward prospective minority employees in all aspects of hiring and employment.

|

| 1966 |

- Oct.

- (Oakland, Calif.) The militant Black Panthers are founded by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale.

|

| 1967 |

- April 19

- Stokely Carmichael, a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), coins the phrase "black power" in a speech in Seattle.

He defines it as an assertion of black pride and "the coming together of black people to fight for their liberation by any

means necessary." The term's radicalism alarms many who believe the civil rights movement's effectiveness and moral authority

crucially depend on nonviolent civil disobedience.

- June 12

- In Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court rules that prohibiting interracial marriage is unconstitutional.

Sixteen states that still banned interracial marriage at the time are forced to revise their laws.

- July

- Major race riots take place in Newark (July 12–16) and Detroit (July 23–30).

|

| 1968 |

- April 4

- (Memphis, Tenn.) Martin Luther King, at age 39, is shot as he stands on the balcony outside his hotel room. Escaped convict and committed

racist James Earl Ray is convicted of the crime.

- April 11

- President Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1968, prohibiting discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing.

|

| 1971 |

- April 20

- The Supreme Court, in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, upholds busing as a legitimate means for achieving integration of public schools. Although largely unwelcome (and sometimes violently opposed) in local school districts, court-ordered

busing plans in cities such as Charlotte, Boston, and Denver continue until the late 1990s.

|

| 1988 |

- March 22

- Overriding President Reagan's veto, Congress passes the Civil Rights Restoration Act, which expands the reach of non-discrimination laws within private

institutions receiving federal funds.

|

| 1991 |

- Nov. 22

- After two years of debates, vetoes, and threatened vetoes, President Bush reverses himself and signs the Civil Rights Act of 1991, strengthening existing civil rights laws and providing for damages

in cases of intentional employment discrimination.

|

| 1992 |

- April 29

- (Los Angeles, Calif.) The first race riots in decades erupt in south-central Los Angeles after a jury acquits four white police officers for the

videotaped beating of African American Rodney King.

|

| 2003 |

- June 23

- In the most important affirmative action decision since the 1978 Bakke case, the Supreme Court (5–4) upholds the University of Michigan Law School's policy, ruling that race can be one

of many factors considered by colleges when selecting their students because it furthers "a compelling interest in obtaining

the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body."

(See also: Affirmative Action Timeline.)

|

| 2005 |

- June 21

- The ringleader of the Mississippi civil rights murders (see Aug. 4, 1964), Edgar Ray Killen, is convicted of manslaughter on the 41st anniversary of the crimes.

|

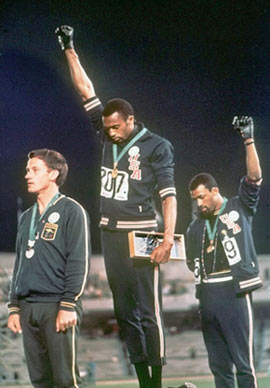

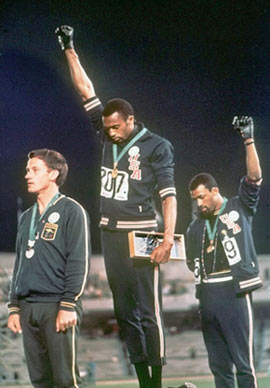

Tommie Smith (center) and John Carlos raise fists for Black Power in

1968. (Source: AP) |

It was the most popular medal ceremony of all time. The photographs of two

black American sprinters standing on the medal podium with heads bowed and fists raised at the Mexico City Games in 1968 not only represent one of the most memorable moments in Olympic history but a milestone

in America's civil rights movement.

The two men were Tommie Smith and John Carlos. Teammates at San Jose

State College, Smith and Carlos were stirred by the suggestion of a young sociologist friend Harry Edwards, who asked them

and all the other black American athletes to join together and boycott the games. The protest, Edwards hoped, would bring attention

to the fact that America's civil rights movement had not gone far enough to eliminate the injustices black Americans were

facing. Edwards' group, the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR), gained support from several world-class athletes and

civil rights leaders but the all-out boycott never materialized.

Still impassioned by Edwards' words,

Smith and Carlos secretly planned a non-violent protest in the manner of Martin Luther King, Jr. In the 200-meter race, Smith won the gold medal and Carlos the bronze. As the American flag

rose and the Star-Spangled Banner played, the two closed their eyes, bowed their heads, and began their protest.

Smith

later told the media that he raised his right, black-glove-covered fist in the air to represent black power in America while Carlos' left, black-covered fist represented unity in black America. Together

they formed an arch of unity and power. The black scarf around Smith's neck stood for black pride and their black socks (and

no shoes) represented black poverty in racist America.

While the protest seems relatively tame by today's standards, the actions of Smith

and Carlos were met with such outrage that they were suspended from their national team and banned from the Olympic Village,

the athletes' home during the games.

A lot of people thought that political statements had no place in the supposedly

apolitical Olympic Games. Those that opposed the protest cried out that the actions were militant and disgraced Americans.

Supporters, on the other hand, were moved by the duo's actions and praised them for their bravery. The protest had lingering

effects for both men, the most serious of which were death threats against them and their families.

Smith and Carlos,

who both now coach high school track teams, were honored in 1998 to commemorate the 30th anniversary of their protest.

An

interesting side note to the protest was that the 200m silver medallist in 1968, Peter Norman of Australia (who is white),

participated in the protest that evening by wearing a OPHR badge.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was used as a meeting-place for civil rights leaders such as Martin

Luther King, Ralph David Abernathy and Fred Shutterworth. Tensions became high when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

(SCLC) and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) became involved in a campaign to register African American to vote in Birmingham.

The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was used as a meeting-place for civil rights leaders such as Martin

Luther King, Ralph David Abernathy and Fred Shutterworth. Tensions became high when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

(SCLC) and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) became involved in a campaign to register African American to vote in Birmingham.